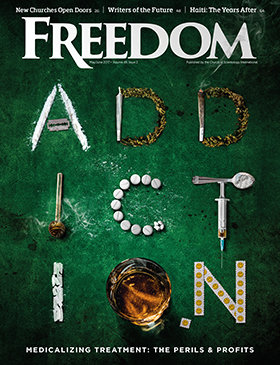

I went to a Narconon center and spoke to three recovering drug users. These stories inspired me to believe there is a solution to addiction.

At a certain point, I could smell the mornings again,” says Derrick. “I set my alarm for 7 in the morning now, just so I can smell the dew come off the ground. I love it.” That’s something Derrick was never able to do when he was addicted to heroin.

Fifteen minutes after the sun slips above the east horizon, at 7 a.m., the first impression I comprehend is green. A pervading, calming, refreshing, life-giving green, the color of new life, enveloping everyone and everything from the spacious tree-covered pasture stretching as far as the eye can see to the rambling residential outpost building with its cozy green interiors.

Welcome to Narconon Suncoast, part of a worldwide network of centers delivering the Narconon program. Narconon—a clever morph which translates into “no narcotics”—is a unique, highly effective drug and alcohol rehabilitation program that, for over 50 years, has been helping individuals live drug-free.

Narconon is not a 12-step program. Narconon does not consider the individual is an addict for life, and it does not regard addiction as a disease. Narconon substitutes the word “student” for addict.

The program is, instead, a precise, strictly organized regimen addressing all aspects of addiction and its students: discovering the real motive, the reason drugs were embraced in the first place and, then, shining a flashlight through the fog of why the student can’t stop, eventually transforming the pain of progress into the deep happiness of real rehabilitation.

This is a place where miracles are said to happen every day. This was just one day in the life of Narconon, impressions from a tour of one of the state-of-the-art facilities and a chance to hear stories from interesting people from all walks of life and countries of the world.

The entry road travels into a horseshoe drive fronting the open reception. There, at 9 a.m., a smiling face welcomes me. A sign-in book and my guide wait. A nearby nook to the right features comfortable chairs facing an audiovisual display where guests are taken through a documentary on the distinctive components of Narconon, a smart walk through the precise phases: 1) Drug-free Withdrawal; 2) New Life Detoxification; 3) Objectives; and 4) Life Skills.

Angela required an intervention to make it from her life in Michigan all in shambles to the peace and seclusion of Narconon. “I walked into the house that day and everyone was there,” she recalls. “My whole family, my kids, all the staff from the dental office I worked at—and there was one guy I didn’t know.” Angela’s first thought was, “Oh, hell no,” and she made a feeble attempt to get something from her car. Luckily she was persuaded to sit down with the group of her closest supporters to have a talk.

“We want the old mommy back,” said one of her three kids, aged 9, 10 and 13, “the mommy that we can play with, that’s not mad at us all the time.”

Angela was no street junkie; standing before me as if she were the all-American bright, happy young mother, clean makeup and shoulder-length chestnut hair, it would be impossible to see her as an addict. One would expect her to be pushing a shopping cart with three kids trailing along begging for sweets. She could be a dentist’s assistant—not a 36-year-old drug addict with a 10-25 pain-pills-a-day habit, whose store was the street and whose life was disappearing way ahead of her time.

Narconon is not a 12-step program. Narconon does not consider the individual is an addict for life, and it does not regard addiction as a disease. Narconon substitutes the word “student” for addict.

Her problem started in her teens with legally prescribed opioid painkillers. An athlete, she sustained a major back injury during a taekwondo match. Shockingly, she found herself almost immediately abusing her Vicodin and it soon no longer numbed her pain. No matter, she was prescribed Adderall, too. Soon she says, “I was buying pills to chase that first high” and her life sank into a desperate daily fight to stop the pain.

“If I didn’t take them I would be sick,” she says now. “They turned me into this aggressive, angry person.” When she added alcohol to the equation, her family became alarmed.

Still, she fought against help, expressing disdain for friend and family pleas to help end their pain. “I wouldn’t have any of it,” she said, “until Kirk spoke. He had been through the Narconon program himself and he told me, ‘Do this for you. Do this for you first, and then for everyone else.’”

“Before that, everyone had been saying I should change for them, I should do this for them, but I realized that this is for me, and I should do it for my own well-being.” Denial gone, commitment honed, Angela was on a plane from Michigan to Narconon Suncoast in Clearwater, Florida, that same evening.

Walking down a few hallways, out into the open-air deck, we turned to a dedicated withdrawal space. Here students receive one-on-one expert care to make it through withdrawal. Within 48 hours of arriving, all students are visited by a physician who assesses medical needs and delivers direction. A registered nurse is on duty, 24 hours a day.

Withdrawal Specialist Tyler Davis explains how specifically tailored vitamin regimens are used to ease the process: “While vitamins take a bit longer than using replacement drugs, the difference is that vitamins actually repair the damage drugs have done to the body—drugs mask it.”

Special techniques used during the withdrawal step—called assists—ease the painful symptoms. Davis explained that a person loses touch with his own body with the use of opiates: “It pretty much numbs everything. Assists help,” says Davis, “ease the transition from being numb to feeling your body again.”

Davis, himself, was an opioid addict before completing the Narconon program two years ago; now he’s certified to assist others. I would have never thought he was a user. His face was clean-shaven, hair close-cropped, skin fair, blue eyes clear, no stereotypical tattoos in sight. Perhaps, the only telltale clue was the passion in his voice: “Helping someone through withdrawal is all about actually communicating with the person—showing them that someone cares about them; that their life matters.”

Off to the next location, I followed my guide through a midmorning sun-spattered patio featuring relaxing wood and canvas furniture, past the ping-pong table (“a favorite” among the residents) and into the New Life Detoxification (NLD) area.

There is room to breathe here, lots of room. The area is huge. A reception to the right was manned by a friendly fellow who greeted us immediately. We sat at another cozy mini-theater. Here, everyone starting the New Life Detox views a presentation which shows that the NLD is based on L. Ron Hubbard’s breakthrough discovery that LSD residues apparently remain trapped in the body, mainly in the fatty tissues, long after a person has stopped taking the drug. This explains why someone who had used LSD in the past could suddenly reactivate a “trip” even years later. Further research revealed that many other toxic substances could also remain in the body, producing negative effects for years to come.

This step is a combination of exercise, sweating in a dry-heat sauna and a carefully monitored regimen of hydration and nutrition. These procedures break up and flush out the toxic residues that can still remain in the body long after the person has stopped taking drugs.

As I looked around, I could feel my personal stereotype of a “drug addict” was changing. There was nothing unusual about these students. They were people you might see anywhere. A row of treadmills lined the wall all the way to the end beyond the reception and two huge saunas, able to accommodate 20 people at once, filled the other. As I peered inside the sauna windows, smiling, sweaty faces waved back—clearly entertained by the visitors squinting through the steamy glass.

“The drug addiction just took everything apart. I have five friends who went to Narconon in Italy 10 years ago, and they’re still clean. So, of course, I came to Narconon here in the U.S.”

Alessio

This is where I meet Alessio. Alessio’s Italian accent and manner are unmistakable. He was a chef and co-owner of a well-known stateside Italian restaurant serving “pizza, pasta—all of it,” and he fits the part perfectly. Married and a father of three, he says it all went down the drain when he sought the wrong crowd to handle his low self-esteem.

“The drug addiction just took everything apart.” But, lucky for Alessio, he had a place to go: “I have five friends who went to Narconon in Italy 10 years ago, and they’re still clean. So, of course, I came to Narconon here in the U.S.”

Alessio, who used a wide range of drugs from cocaine and heroin to marijuana and Suboxone during his downward slide, says the sauna helps you to “stay clean.”

“With the sauna, I experienced an amazing effect. You do feel the drugs coming out. You sense your body becoming clean, your skin becomes better, more clear. It gives you a heightened sense of awareness too. For me [the sauna] is the most important part.”

All this talk of Italian cooking started my stomach rumbling, and surprisingly it is already noon, time for the whole Narconon campus to enter the dining room. We pass through the enormous rec room (sporting a pool table, bookshelves, several couches and a giant plasma TV). It is hard not to be a little jealous of the facilities available for those going through rehab here. On the floor in front of the plasma TV, spread out on the comfortable-looking carpet with a few pillows and a blanket, a carmel-skinned man in a fresh white T-shirt and jeans is resting with his 10-year-old son curled up next to him. They were watching an action movie together.

“It really truly saves your life. Not only yours but your family’s. It’s a total 180.”

Angela

Noting my slightly perplexed expression, our guide explained the father was in the program, but family visits are encouraged to “help create bonds and relationships that may not have been possible while the family member was on drugs.” I thought to myself the father I had just seen did not look like an addict—but I guess he wasn’t one. He was a student.

Coming into the dining room we caught the last few strains of “Happy Birthday” before staffers and students alike broke out into hoots and applause for one who had turned another year older. Eight round tables in two neat rows held staffers and students all together as they dug into a delicious meal. The chef who prepares all the meals came from the Sandpearl Resort, a Clearwater Beach five-star hotel. Now, with his own kitchen, he provides everyone with three delicious and nutritious meals a day, plus snacks.

Today’s meal, Crawfish Étouffée. A Cajun dish of seafood and buttery spicy sauce, it was complemented nicely by steamed white rice and crisp green broccoli. I cleaned my plate and enjoyed a side of salad from the buffet to boot. Delicious. If only I could have a five-star chef cook for me every day.

Much too soon, lunch was over, and I brought my plate to the busing station. “I can take that,” says Alessio with his Italian accent. “It’s hard to keep him out of there,” said our guide, noting that while Alessio was doing the program, he still helped in the kitchen.

Classes start again and will go to 9 p.m. tonight, save a break for dinner. We won’t be able to go inside, but we look through the tall windows of the objectives classroom.

[LIFE SKILLS] is where a person can address the reasons they turned to drugs in the first place.

People in teams of two walk around the room pointing out objects. Objectives are procedures to direct attention away from past memories and onto present and immediate surroundings. Being stable and in the present is considered a vital step to helping students remain drug-free.

To the right there’s a balding older man with a potbelly and a small pair of spectacles perched on his nose, working with a shorter middle-aged woman, whose graying hair is pulled away from her gently lined face into a ponytail. There are a couple of jocks in the corner, ripped arms bulging in their Narconon outfits as they walk around the room, one clearly tattooed, the other not. A young kid, maybe in his late teens, with sandy blond hair, walks past the window and waves happily at us. Could they all really be addicts? No, they are students.

Derrick, who told us he had been up since 7 a.m. just to smell the morning dew, was on a break at the moment, giving Freedom a chance to discuss his experience with objectives.

A former Marine who left the service just three years ago, Derrick still bears the straight stance and square shoulders of a trained fighter. After several tours in Afghanistan, he found assimilating back to civilian life challenging. He turned to heroin as a solution: “That stuff is a beast,” he says. “It grabs hold of you and won’t let go.”

Soon the solution became the problem, “I couldn’t do my own laundry and dishes without getting high. I couldn’t get groceries without being high.” Derrick said he started to think “something was wrong with me” because he couldn’t do normal everyday functions “without being high.” Thankfully, the love of his wife and sister brought him to Narconon to get help.

Objectives are “cool” he says. “As humans, we can have thoughts about thoughts. Objectives helped me to become aware of my emotions.” He says objectives “give you a chance to explore the real you and who you really are.” While doing objectives daily, Derrick says the process opened up his mind “enough to get my creative juices flowing. I wrote a book, just a short one, while I was on them,” and he mailed it to his mom and sister to show off his newfound artistic talent—previously buried by a drug-induced haze.

Now well on his way to recovery, Derrick has a message for his fellow veterans: “I know we’re all pretty ‘crazy’—but you got to channel that into something positive. If you put all your effort into something positive, then the sky is the limit!”

Out the window, afternoon shadows fall across the green countryside as we walk down long hallways past manicured rooms. Next stop, Life Skills.

This is where the polish work is done. Once the drug cravings have been eliminated and the physical side of addiction is gone, this is where Narconon students can address the reasons they turned to drugs in the first place.

As we walk in, the room is quiet despite the diverse crowd. Each student is doing self-study while a Narconon staff member answers questions. One of the courses, explains the guide, helps you to spot factors that have a positive influence in your life and those that do not.

Derrick mentioned he had worked one-on-one with a Narconon staff member on this and learned to recognize the situations that got him into drugs in the first place and those that had badly influenced his life. Likewise, through Life Skills classes, Angela learned to address the horrible fact that her biological mother had not been a good influence when she literally sold Angela methadone pills to “pay for her own crack.” The practical coursework is set to instill the life skills needed to succeed after a student leaves this rehabilitation paradise and returns to the real world.

The sun doesn’t set until about 8 p.m. this time of year, but it was nearing the far horizon as we all advanced to dinner. Talk and laughter wafted out of the dining room; the gentle clicks of tableware kept rhythm as the Narconon team dug into their barbecued ribs. The ambience was that of a big mismatched family, which had come together through “a common history and a common goal,” as Davis put it.

Wrapping up our tour, we stepped into the auditorium. Walking in, I could almost feel myself expanding. There was so much space provided by the double ceiling and faraway walls. Able to fit 281 people at once, the cream paint, warm dark wood and green accents create a beautiful space to hold gatherings and graduations.

About once a month students and staff converge in this spot, joined by visitors and proud families to hear their loved ones speak at their Narconon graduation. It’s a very emotional experience: “I’ve never seen my dad cry before. But he cried at my graduation,” said a former student. “He told me the best things that happened to him this life was when I was born, and when I graduated Narconon.”

By 9 p.m. the sun’s light was gone, the fresh greens outside had turned dark, mixing with the purple hues of nighttime. Lit by small lanterns along its length, a running path twists through the grounds. Groups of students gather on the lighted patio to watch the moon rise or hang out in their rooms, curled up with a book. Being in bed with lights out isn’t until 11:30 p.m. so there’s a bit of time to relax.

How should I sum this all up?

“It really truly saves your life. Not only yours but your family’s. It’s a total 180. If you are struggling or hurting, it will help you physically and mentally for sure. Narconon helps you live a happy, healthy life,” says Angela.

“The solution is to come here,” says Alessio. “There are no words for that. Only, come and see for yourself.”

(Editor’s note: The names of Narconon students have been changed to protect their privacy.)