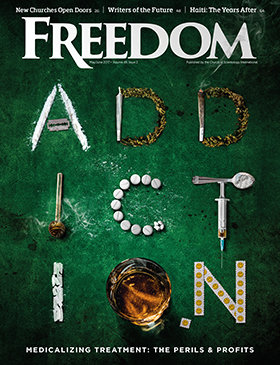

From New Jersey to West Virginia to Mississippi, there are no boundaries in a nationwide epidemic. The opioid epidemic had its roots in a New England medical journal, was set in motion in a Connecticut lab, found its epicenter in West Virginia, and soon spread throughout the country. Pain pills kicked open the door to addiction, and heroin soon stormed through the easy entry. Every gender, race, age, occupation and economic level has been affected. Each story is different, though most have something in common. All 50 states have suffered overdose deaths and broken families. All the stories are heartbreaking. Here are just three of them.

The Secret

Debbi Hambers Ward, 46, remembers the surprise she felt the day she learned her 18-year-old daughter Dallas—suddenly in critical condition in a hospital suffering organ failure and facing immediate open-heart surgery—had a terrible secret.

In the days before, Dallas, the young mother of a year-old daughter, had complained of severe pains in her joints and legs. She’d grown inexplicably weak and doctors suspected arthritis. But the condition grew worse and by the time she ended up in a hospital in Tupelo, Mississippi, she was in serious condition. The doctors placed Dallas in a coma; they told Debbi they would have to replace two of her heart valves and put in a pacemaker. Dallas had a MRSA infection—a drug-resistant form of staph bacteria—that had lodged in her heart.

“This was a total shock,” Debbi said. “I thought we were going to see a rheumatologist.”

They told Debbi to prepare herself—they said Dallas had a very slim chance of making it through the heart surgery. Then the doctors asked a question out of the blue:

“How long has Dallas been shooting heroin?”

That was the first time Debbi learned what was wrong with her daughter.

“I had no idea,” Debbi recalled. But she soon realized it had been going on awhile. “She always wore long sleeves. She did look sick. She would always claim to be cold. The heart doctor was very blunt—he said, ‘She has been using IV drugs for a while.’”

Which answered the mystery of what had led to the infections, the organ failure and a failed heart.

After coming out of the coma, Dallas eventually admitted to her mother that she was a heroin addict. “We didn’t talk about, did you take some prescription medicine at first, or was it just to get high? We talked about the first time a needle was put in her arm.”

Dallas said she had done it at first to impress a boy, then became addicted. Soon she was sharing needles and stealing for drug money. Dallas told her she had tried to stay clean during her pregnancy. But once her baby was born—miraculously free from complications—Dallas was back into it, hard, but kept it hidden. She went to Memphis for drugs.

“I didn’t know where she was,” Debbi said.

Though she survived the MRSA, her struggles continued. Dallas went to five different medically-assisted rehab programs where she was given replacement drugs. She kept using. “When you’re giving a heroin addict pain medicine, … they gave her fentanyl patches, … it didn’t touch the pain,” Debbi said. And it didn’t work. And MRSA returned. She had a second heart surgery.

She was weak and scarred, Debbi said, and she realized the damage had been done. The surgeon told Debbi he wouldn’t “operate a third time in a year,” she said. “And I don’t blame him.”

Dallas was told she had six months to live. “She was detoxing one more time, trying to get clean for as long as she had left,” she recalled. “For 45 days she was clean.”

They celebrated with a trip to Disney World and took Dallas’ younger sister along. She said they tried to find some happy moments away from the inevitable reality they all shared.

“She and I talked a lot on that trip,” Debbi recalls now. They talked about Dallas’ daughter, and about Dallas’ brother, who is two years older and on a different path, getting a doctorate in psychology.

And Dallas talked with her younger sister, who had been witness to what her sister’s life had become.

“The two of them got so close,” Debbi said. “When Dallas was clean, she would tell Delaney (her sister) ‘Don’t ever do this. Don’t ever do anything to impress anyone.’”

And on that trip, Debbi helped Dallas plan for her funeral.

Yet, as soon as they got back, Dallas began using again, stealing from her mother to pay for the drugs.

“I had to make her leave,” she said, a catch in her voice. “Even after she’d stolen everything I owned, … it was very hard to put your dying child on the street.”

Debbi took Dallas’ daughter to raise and Dallas went into hospice care. She came home for her daughter Madelyn’s second birthday.

“Everything was bittersweet. We knew that Dallas wouldn’t be there for the next one,” she said.

In the end Dallas returned to the street where the drugs were. She died on July 17, 2016—roughly three months beyond what doctors had predicted—at the home of a fellow addict. Debbi had not seen nor heard from her for weeks. She learned of her daughter’s death on Facebook.

The casket, the flowers, the music and how she looked, were just as Debbi and Dallas had discussed.

“I did her hair and makeup, and her nails after she passed away,” Debbi said. “I talked to her. I cried. … It was something I promised her.”

A Family Tragedy

A West Virginia state trooper’s navy-and-tan patrol car is parked in front of the red brick building with top lights still flashing. This is Marcum Terrace apartments, a decades-old government housing project in Huntington, home to more overdoses than anyone can count. The trooper, with a Freedom reporter riding along, arrives 30 seconds behind paramedics who have responded to yet another overdose emergency.

Savannah looks down at the woman on the floor. A 21-year-old recovering addict herself, she leans against the refrigerator of her cramped apartment and asks, nearly without emotion, “Is she gone this time?”

Six feet away, paramedics are on their knees working on Misty, Savannah’s 42-year-old mother, unconscious on the floor, and near death. Savannah tells Freedom that this is her mother’s third overdose—that she knows of.

Savannah stands by anxiously. A male friend lingers near her, holding a puppy. Savannah says they found Misty on the floor outside the bathroom in the tiny one-room apartment.

“She wants to go get some more. She’s sick and she won’t get clean. She won’t stop until she’s gone.”

Daughter, after her mother’s third overdose

Paramedics have just administered 2 mg of naloxone and are waiting to see if the antidote has come in time to save her life … again.

Savannah seems dazed, and only now remembers, she says, that there is a dose of Evzio, an auto-injectable antidote, in the kitchen cabinet. She could have injected her mother before the paramedics arrived.

For Savannah, for the trooper and for the paramedics, this is a familiar story. The only thing uncertain is how this one will end. After several moments of silence, there’s a dry cough, then a phlegm-filled cough as Misty’s eyes flutter open.

“Hi Misty,” says the paramedic. “Welcome back.”

They explain to her what happened and remind her where she is. She wants them to leave. But they take her to the hospital to get checked out.

As Savannah explains Misty’s dilemma, she speaks to her own addiction. Savannah says she has been clean for five weeks after going “cold turkey.” But Misty can’t quit.

“She wants to go get some more,” Savannah says. “She’s sick and she won’t get clean. She won’t stop until she’s gone.”

A Teddy Bear in Mayberry

The borough of Allendale, childhood home of former FBI Director James B. Comey, is in the lush, picturesque northeast corner of New Jersey, home to 6,500 people. The Allendale Hotel, now a rooming house, was once a frequent vacation spot for Babe Ruth.

“Allendale is Mayberry,” Gail Feldner Cole told Freedom.

Her son Brendan, a good-looking, well-liked kid, went to a respected all-boys Catholic high school in northeast New Jersey, the same school his dad went to, the same school his older and younger brothers went to. Brendan graduated, went to University of Richmond and was studying to be an equities trader.

He had played high school lacrosse, had gotten hurt one year, had shoulder surgery and was prescribed an opioid painkiller. Then he was prescribed one again for a tonsillectomy at 19. Unbeknown to his family, finishing those prescriptions was enough to get him hooked.

By the time Brendan was in college, he was an opioid addict. He came home for winter break his senior year, and finally admitted to his mother that he had “a little pill problem.”

In truth, his pill problem was behind him. He was already shooting heroin.

By the time he graduated, he had been through rehab a couple of times and was trying to turn things around. He was living with the family again, back in his childhood bedroom, which was still adorned with sports posters, trophies and a teddy bear.

He started a temp job on January 2, a new start for a new year. The next day, Gail said, “He looked the best he had in ages.” He borrowed the car to go to the mall.

“And he came home, and I said, ‘It’s so nice to have you back, B,’ and he looked at me and said, ‘Thanks for giving me another chance.’

“And as those words came out of his mouth, I was like, ‘Oh wow. He’s high!’” she recalled. She immediately knew she would spend the next couple of days finding him a new rehab facility.

Around 1 a.m. that morning, his father passed Brendan’s open bedroom door and immediately knew something was wrong. He screamed. Brendan’s mother and younger brother rushed into the room. There was Narcan—the opioid overdose antidote—in the house and someone administered it to Brendan.

By the time the ambulance arrived—less than 10 minutes after his father’s first scream—Brendan was awake, able to sit up, get out of bed and walk to the ambulance.

Twelve hours later, they returned home from the emergency room where Brendan had been observed, diagnosed, counseled, rehydrated and, in specific detail, warned of the damage he was doing to himself. When they got home, he hugged his mother, thanked his parents for saving his life and for giving him yet one more chance. He said he was ready to turn his life around. He went upstairs to take a nap.

Two hours later, his brother went in to wake Brendan, and knew. Screams brought his parents running. This time, they were too late.

“We pulled him off the bed, and he was gone,” Gail recalled, “two hours after he got out of the emergency room.”

Brendan’s heroin kit, with needles and a spoon, had been hidden inside his teddy bear where the stuffing had been pulled out. He had used again—for the last time.