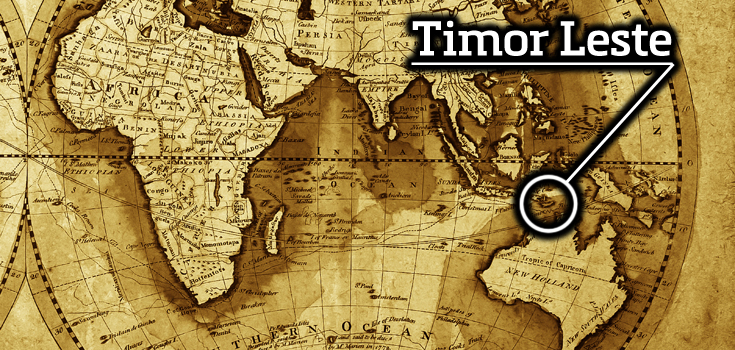

Timor-Leste

Portuguese explorers landed on the island in 1515.

On May 20, 2002, it became the first sovereign state of the 21th century.

Timor-Leste spans 5,400 square miles and constitutes the eastern half of the island of Timor, with a population of approximately 1.18 million.

Dili is Timor-Leste’s capital and largest city.

Portuguese and Tetum are the country’s official languages.

Coffee is one of Timor-Leste’s largest exports, generating $10 million per year, with Starbucks a major purchaser.

Independence and nationhood come with a price. Political upheaval, violence and bloodshed can be part of such a genesis. For Timor-Leste, at the eastern end of the Indonesian archipelago, independence came in the wake of some of the worst atrocities of modern times.

But out of the ashes of that destruction hope has arisen for the future of the first new nation to achieve independence in the 21st century.

A Portuguese colony from the 16th century, Timor-Leste declared independence in November 1975, only to be crushed under the heel of another master almost immediately. Within days, the Indonesian army invaded to begin a 24-year occupation that ultimately killed some 30 percent of the population.

Violence and human rights abuses remained the hallmark of the occupation until 1999, when the United Nations became involved in an effort to bring peace and help the nation rebuild.

The U.N.’s first action was to sponsor a referendum to ask the Timorese people whether they wished to remain part of Indonesia or become an independent nation. Nearly 80 percent voted for independence.

Indonesia-backed militia responded with violence, virtually burning the nation to the ground. Eighty-five percent of the buildings in the country were set aflame; hundreds of thousands of people were displaced at gunpoint; an unknown number, including foreign journalists who took refuge in local churches, were massacred.

The rampage was checked by the arrival of a U.N. peacekeeping force on September 20, 1999, which began to bring the situation under control.

Instrumental in that effort was José Ramos-Horta.

Internationally known as a peacekeeper, Ramos-Horta lived in exile for the duration of the Indonesian occupation. Throughout that time, he traveled the world, speaking out to save his people from annihilation and to bring human rights to Timor-Leste.

He regularly addressed the U.N. Security Council to ensure his people and the brutality they suffered would not be forgotten. Virtually the lone voice for the Timorese outside the country, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1996 for his efforts to bring about “a just and peaceful solution to the conflict in East Timor.”

In December 1999, following the U.N.-sponsored intervention, Ramos-Horta returned to Timor-Leste, and he assumed the post of senior minister of the new government on the restoration of independence in 2002.

But bringing democracy proved daunting as violence continued. In 2006, a group of more than 500 men splintered from the army and retreated to the mountains, from where they organized and launched attacks on cities and villages. Homes were torched by gangs and the prime minister then in power was forced to step down.

As the senior minister and foreign minister at that time, Ramos-Horta was asked to assume the vacant prime minister post. He agreed and set about the task of rebuilding. Establishing new institutions of government, stabilizing the guerilla force into a standing army and educating the Timorese people into the rule of law were paramount.

Also in 2006, the U.N. Security Council set up a new peacekeeping mission, the United Nations Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste. Its role, which included strengthening human rights mechanisms in the government, would continue until December 31, 2012.

Ramos-Horta was elected president of Timor-Leste in May 2007. Gradually, despite continued turbulence, including an assassination attempt in 2008 that wounded Ramos-Horta and one of his guards, peace and order began to prevail.

As the first new democracy of this millennium, Timor-Leste was founded on many of the rights and freedoms broadly recognized in the latter half of the 20th century. Thus, the rights contained in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights were integrated into its constitution.

But building a lasting peace requires more than ending abuses; it also involves ongoing education, particularly of youth, on human rights principles to provide a foundation for future stability. The solution was again the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, this time backed by a multimedia educational program that included public service announcements and educator kits containing complete lesson plans and instructions.

Materials for this campaign were provided by Youth for Human Rights International, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to teach young people about human rights to help them become advocates for peace.

In 2009, the group’s president, Mary Shuttleworth, visited Timor-Leste as part of a global tour to educate youth on the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“It was heartbreaking to see the violence this population, including the children, had suffered in their time. Every family had a horror story of gross human rights abuses,” said Shuttleworth. “Everyone had lost a father, an uncle, a brother. Building a modern nation on top of that history would be a daunting challenge for any leader.”

The first step of the program was to distribute booklets in Portuguese describing the rights in the Declaration. The next hurdle was to translate the program’s materials into Tetum, the language spoken by more than 85 percent of the population.

With the help of the U.N. human rights team and the Tetum Language Institute in Dili, Youth for Human Rights International’s What Are Human Rights? booklet, public service announcement videos—one for each of the articles of the Declaration—and educator’s guide were translated into Tetum.

Training sessions were given to human rights nongovernmental organizations and youth clubs. Trainers and student leaders were briefed on the materials and coached in teaching human rights with a message coined by the young Timorese themselves: “Stand up for peace, discrimination no!”

In its initial phase, Youth for Human Rights distributed tens of thousands of booklets on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as over 200 educator packs in Tetum and English, including educational films.

Those Timorese youth leaders trained numerous others in groups and associations across the land in how to educate youth and adults alike on the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

From community centers to schools and social clubs, these human rights trainers were supplied with Youth for Human Rights educational materials in their own language and have since brought the program to thousands of Timorese across all levels of society.

“Working together with the United Nations mission and other groups, we were able to empower the Timor-Leste human rights groups to bring awareness of the Universal Declaration to their communities,” said Nigel Mannock, a spokesperson for Youth for Human Rights.

When the U.N. mission concluded its work and withdrew from the country, it left behind a network of groups dedicated to protecting and furthering human rights, many of which became Youth for Human Rights chapters.

The U.N. mission acknowledged Youth for Human Rights for its achievements in supporting the promotion and education of human rights. A U.N. representative wrote in a letter to Youth for Human Rights International: “I would like to take this opportunity to express my heartfelt appreciation to Youth for Human Rights International for the work, support and cooperation with our organization in fostering increased awareness of human rights in Timor-Leste.”

Youth for Human Rights has continued its work to increase knowledge of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights among Timorese youth. Timorese human rights trainers, supplied with Youth for Human Rights educational materials in their own language, are bringing the human rights program to thousands across all levels of society.

To date, more than 50,000 What Are Human Rights? booklets have been distributed throughout the country, as have hundreds of educator’s guides.

“Human rights education has improved since we arrived in Timor-Leste. Crime and violence have decreased and the country is following the path to stability,” said Shuttleworth.

Today, Timor-Leste enjoys a well-earned peace. Literacy levels have improved, unemployment has plummeted and the economy is gaining strength, with double-digit growth for three consecutive years. The fruits of the country’s leadership are evident throughout the island.

“Dili is very different from when I went there in 2009,” said Mannock. Unlike those times, he noted, today “you will find Timorese and Indonesians working side by side.”