The Attention-Deficit Fraud

In just 20 years, ADD and ADHD have gone from relatively rare diagnoses to “disorders” allegedly suffered alone or in tandem by nearly 20 percent of children aged 4 to 17 in the United States.

Meanwhile, sales of stimulant drugs prescribed to treat these conditions increased from $40 million a decade ago to $10 billion in 2013. And yet, according to experts, no science exists to show either of these are real conditions.

Long neglected by the media, many journalists today question whether “attention deficit” is anything more than a spurious label concocted by the psychiatric industry as an underhanded and imminently dangerous marketing tactic. Parents, too, are starting to reject the branding of normal childhood behavior as “diseases,” with brain-damaging drugs prescribed to treat it. And, perhaps most poignantly, the “medicated” kids themselves are starting to push back, as you’ll see in the story of one young boy who refused to comply with his regimen and, in doing so, saved himself.

It Just Doesn’t ADD Up

Results

Results

Having a little trouble making it through this sentence without your mind wandering? Maybe you have ADD. Do you sometimes feel like diving headfirst onto your sofa instead of calmly sitting down—you know, just for kicks? Now it’s sounding more like ADHD. Either way, medication is indicated.

There are a number of drugs to choose from: Concerta, Strattera, Adderall…. Yes, Adderall is good for symptoms like yours. Here’s a sample pack to get you started, and a script for when those run out. Got it? OK. Check back in a month.

Sound a bit simple? A little quick for a diagnosis of something as nuanced and subjective as a “behavioral disorder”? Somewhat casual for a weighty recommendation like starting a course of powerful, addictive stimulants?

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the chances of a child between the ages of 4 and 17 receiving a diagnosis of Attention-Deficit Disorder (ADD) or Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are one in five. And of those diagnosed with ADHD, nearly 70 percent will be prescribed a powerful stimulant like Adderall or Focalin—the possible adverse effects of which include insomnia, mood issues, loss of appetite, psychosis and more.

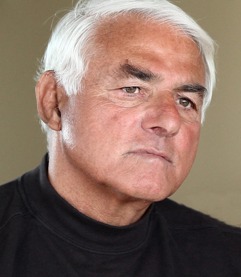

“We’ve taken normal development and turned it into a mental disorder. The drug companies are getting wealthy on the backs of millions of vulnerable kids who have no business being diagnosed with anything.”

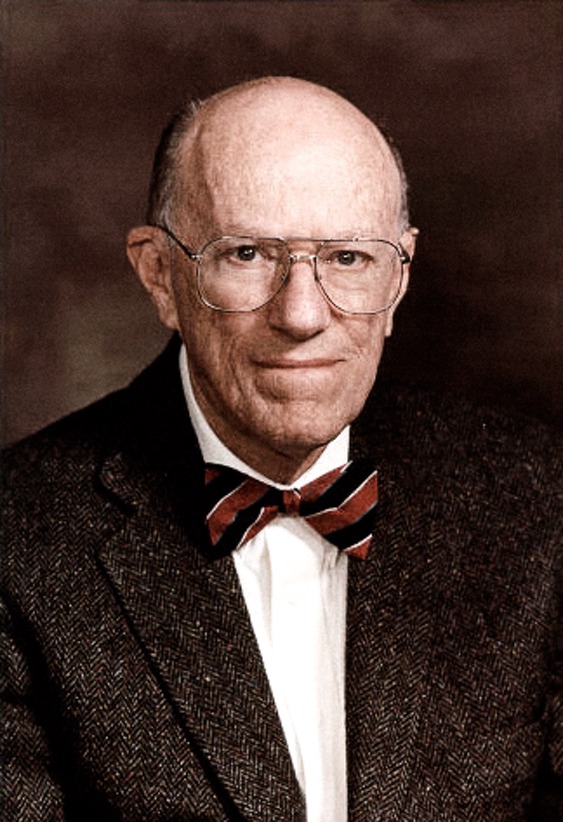

Dr. Allen Frances, Professor Emeritus of psychiatry, Duke University

In 2013, an estimated 6 million American children had an ADHD diagnosis, a 40 percent increase from a decade ago. And the CDC reported in May 2014 that more than 10,000 American toddlers as young as 2 years old are being drugged for the condition with powerful speed or amphetamine-like substances such as Ritalin and Adderall.

Even some who had prescribed—and profited—from these prescribing practices were shocked and appalled at this news, using words like “malpractice” and “travesty” to characterize the administration of drugs to what are essentially babies.

An increasing number of mental health experts are coming to the conclusion that the ADD/ADHD train has gone off the rails, that these are not even actual, legitimate disorders, and that the operation has been co-opted by the pharmaceutical industry as a means to justify zealously peddling drugs for astronomical profits.

Sales of stimulant medication, which stood at $40 million 20 years ago, now approach a staggering $10 billion annually. The overwhelming majority of “customers” are children and adolescents being treated for impulsiveness, inability to concentrate, restlessness and occasional malaise—characteristics of normal children and normal behavior—giving rise to the idea that the “condition” we’re trying to cure is childhood itself.

“We’ve taken normal development and turned it into a mental disorder,” said Dr. Allen Frances, professor emeritus of psychiatry at Duke University and author of the book Saving Normal: An Insider’s Revolt Against Out-of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life.

“The drug companies are getting wealthy on the backs of millions of vulnerable kids who have no business being diagnosed with anything. It’s pure greed. They’re conducting an uncontrolled experiment without informed consent on a vast army of kids who have no clue what these powerful medicines are doing to their young brain.”

Frances’ view on medicating children, and on the suspicious alliance of the psychiatric and pharmaceutical industries, isn’t revolutionary. The Church of Scientology and Citizens Commission on Human Rights, for example, have been reporting on the issue, and exposing improprieties and abuses, for more than two decades. The New York Times now considers the problem so serious that it assigned a dedicated reporter (Alan Schwarz) to cover it nearly fulltime.

ADHD can’t be proven, disproven or definitively diagnosed. As is the case with almost all purported mental diseases, no definitive tests exist. The diagnostics criteria are subjective, and the symptoms are vast, varied and native to the human condition—every person has them sometimes, to some degree.

The rise of ADHD diagnoses and prescriptions for stimulants coincided with a marketing campaign for sales of ADHD drugs, which have increased more than five times in the past decade.

It’s been reported that the “father” of the ADHD diagnosis, Leon Eisenberg—described as a “psychiatry and autism pioneer”—allegedly admitted on his deathbed that ADHD was a “fictitious disease” never actually proven to exist, a loose theory elevated to a diagnosis as a means to peddle pills.

Even those who believe the condition is real are sounding the alarm that it is irresponsibly diagnosed—with disturbing regularity.

As the New York Times reports, the American Psychiatric Association receives much of its financing from drug companies, suggesting it has a vested interest in casting the widest net possible to define the “conditions” that might lead to an ADD or ADHD diagnosis. And a wide net it is: diagnostic criteria include “makes careless mistakes” or “has difficulty waiting his or her turn.”

“It’s the medicalization of nearly all child behavior,” said Joel Nigg, professor of psychiatry at Oregon Health and Science University.

Dr. Frances describes the numbers of kids wrongly diagnosed and needlessly medicated as “dangerous and outrageous.”

“There is also no proven long-term academic benefit to taking the medications,” Frances continued, “even though that’s how they’re being sold—‘Take these and your kid will be a far better student.’ Yet the same parents who would never allow their child to take steroids to be a better football player think nothing of giving stimulants to perform better in school. Here’s the best way to help them be better students: Smaller class sizes and more gym teachers.”

Administering drugs to a child of course requires the active participation of the parents, who have little understanding of the true nature of the drugs, and question marks around their efficacy and their many adverse effects.

Professor Nigg describes a scenario he’s seen countless times: “Picture a clinician sitting there in his office with a frantic parent whose child is all over the place,” he said. “The kid doesn’t seem able to handle the stresses of everyday life. The family is economically stressed. You have two choices: Do nothing or prescribe something. Is it a quick fix? Yes.”

What about alternatives? Are they not even on the table?

Many doctors, such as Doris Rapp, M.D., author of Is This Your Child? and other works, recommend a complete physical examination since behavioral manifestations often are rooted in improper diet, an allergy or some other tangible cause.

But many times, Nigg said, “the parents are overwhelmed by two jobs and a sick grandmother” and simply agree to the use of drugs.

Dr. Nancy Rappaport, child psychiatrist and director of school-based programs at Cambridge Health Alliance near Boston, admits that the quick-fix solution of drugs for children that are often administered cavalierly, and without even a thorough diagnostic workup, is greatly troubling.

The FDA’s label on Adderall XR includes the warning: “Amphetamines have a high potential for abuse... Misuse of amphetamine may cause sudden death and serious cardiovascular adverse events.”

“Some kids simply are oppositional by nature,” Dr. Rappaport said. “When you tell them to do something, they tend to defy authority. Yet we have taken to labeling that as something in need of medicating. Maybe the fact they have difficulty concentrating in class is due to the fact the material is boring, they sit in seats all day, and they have a problem with being given orders. That does not mean they need drugs to comply and in fact it’s irresponsible to prescribe them.”

It is perhaps telling that one of the drugs most commonly prescribed to children—the stimulant Adderall—recently celebrated its 20th anniversary on the market. Roger Griggs, the pharmaceutical executive who introduced it, named it by combining the quasi-acronym “ADD For All,” ultimately coming up with “Adderall.”

Pharmaceutical manufacturers have enjoyed massive success with such catchy, consumer-friendly labels for their chemical concoctions, which they are permitted to advertise in magazines and on television, radio and the Internet. Direct-to-consumer marketing has led to skyrocketing use of prescription medication in the last decade—not just psychotropics, but all behind-the-counter drugs.

It comes as little surprise that pharmaceutical companies like Eli Lilly work diligently with psychiatrists to concoct more conditions and drive diagnoses that indicate medication. The latest of these to emerge, and call for treatment with drugs, is Sluggish Cognitive Tempo (SCT), largely indistinguishable from ADD, characterized by inattention, lethargy, distractibility and poor organizational skills—in other words, being a child.

Dr. Frances calls SCT “the stupidest idea I’ve heard in 40 years of dealing with stupid ideas. It isn’t merely financially motivated, it’s absurd. It’s just a blind grab to exploit millions of additional kids. I mean, kids are the best customers in the world, because if you play it right they’ll be there for life.”

Most medicated children have little choice in the matter, particularly those in the foster care system. A groundbreaking and alarming year-long investigation by San Jose Mercury News reporter Karen de Sa found that nearly one in four adolescents in California foster care received drugs to better control their behavior—more than three times the national rate.

De Sa found that over the last decade, almost 15 percent of the state’s foster children of all ages were prescribed psychotropic medications. Of those, 60 percent received at least one antipsychotic.

Hearing statistics like these leaves Dr. Frances shaking his head and reiterating that parents need to be vigilant and become better protecters of their children in a country that increasingly seems to believe there is a chemical elixir to fix every negative action. “There is no magic to these pills,” he cautions. He noted they can be “profoundly destructive.”

A touch of good news has emerged, however, amid the prescription epidemic. The impact of the Mercury News series resulted in tightened restrictions on the drugging of all underprivileged children in California, not merely those in foster care.

Beginning October 1, a new rule went into effect that requires a state pharmacist to review every antipsychotic prescription before the drugs can be dispensed to any child who is 17 or younger and covered by Medi-Cal, the state’s health program serving low income and foster families.

“This, the medical poisoning of millions upon millions of medically normal children worldwide is the greatest healthcare fraud/crime since the beginning of the 20th century,” said Fred Baughman Jr., M.D., a California neurologist.