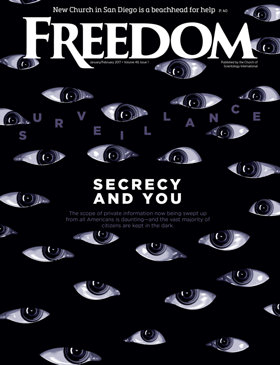

For years, Ernest Hemingway was haunted by the idea that “Feds” were shadowing him. His obsession led those closest to him, including his wife and family doctor, to persuade him to see a New York psychiatrist and ultimately to check into the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where, in late 1960, the Nobel Prize–winning author received the first of two courses of electro-shock “treatments” from psychiatrist Howard Rome.

The first battery of up to 15 shocks devastated him. “What is the sense of ruining my head and erasing my memory, which is my capital, and putting me out of business?” a broken Hemingway told his friend and biographer, A.E. Hotchner. “It was a brilliant cure but we lost the patient.”

On July 2, 1961, just days after his release from the clinic following the second volley of shocks, Hemingway killed himself in his Idaho home.

Through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the FBI in the 1980s, Freedom obtained the bureau’s dossier on Hemingway, with documents showing that, indeed, federal agents had been keeping tabs on him from as early as the 1940s, when Hemingway lived in Cuba and had organized local resources into an informal anti-Nazi intelligence network whose existence offended FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.

Hoover responded by directing his men in Havana to assemble “any information which you may have relating to the unreliability of Ernest Hemingway.”

Up to 1966, journalists, researchers and the average citizen had no guaranteed right to access the files of any government agency. But that changed on the Fourth of July anniversary that year, when the Freedom of Information Act was signed into law.

U.S. Congressman John Moss, acknowledged as the father of the Freedom of Information Act, had campaigned for the measure for more than a decade. His hard work helped to establish a fundamental right that is now recognized in the same family of freedoms as that of speech, religion, assembly and others.

On June 30, 2016, President Barack Obama marked FOIA’s golden anniversary by signing the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016, a measure that bolsters freedom of information in many areas. Passed unanimously by the Senate and the House, the new law provides reforms that add teeth to the act and help to increase transparency in government.

Over the decades, Freedom and the Church of Scientology have utilized existing laws to bring to light information in the public interest. In the 1970s and early 1980s, for example, Freedom published a series of articles based on FOIA documents that exposed involvement in production of chemical and biological warfare agents by military and intelligence agency personnel, and testing of those agents in numerous venues across the United States—all carried out without the knowledge or consent of citizens in those areas.

Tests exposed by Freedom included the release of swarms of mosquitoes—of a strain that can carry both yellow fever and dengue fever—in Georgia, as well as a range of other chemical and biological warfare experiments in New York, Texas, Indiana, Maryland, Washington, D.C. and elsewhere.

Journalist Jimmy Breslin devoted one of his Newsday columns to condemning a New York test exposed by Freedom: “Only the Church of Scientology thought enough of it to press the government.”

Over the decades, Freedom has provided a forum for the views of some of the most respected authorities on freedom of information, including Quinlan Shea, former director of the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Privacy and Information Appeals during the administrations of Presidents Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter, and Congressman Moss himself, to whom the magazine presented its Human Rights Leadership Award in 1992.

To share their expertise on use of the FOIA, the editors of Freedom prepared, published and distributed, free of charge, guides to the general public on how to submit FOIA requests and obtain records in separate editions in 1976, 1979 and 1989. A new edition will be issued in commemoration of the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016. They also have continued their advancement of FOIA issues through regular coverage in the magazine.