Peak Performance

When Daniele Nardi hears that something hasn’t been done, can’t be done, will never be done, that’s his cue to get it done.

So it was in January that Nardi, a world-class mountaineer and rock climber, set out to conquer Nanga Parbat, the western anchor of the Himalayas in Pakistan, and one of 14 “eight-thousanders”—mountains that rise more than 8,000 meters (26,247 feet) above sea level and whose summits are in the death zone, altitudes with insufficient oxygen to sustain human life.

Nanga Parbat is the world’s ninth highest mountain, and is notoriously difficult to climb. Nicknamed a “killer,” it has never been summited in winter—when conditions are infamously hostile, with temperatures as low as -58 Fahrenheit and sustained wind speeds reaching 75 miles per hour.

“The real joy of the challenge is in pushing beyond your limits,” Nardi said in an email interview through an interpreter. “I love to climb these peaks because they make me feel naked, they make me feel alive. I also like to feel I am an example for the younger generation to follow.”

Nardi has served as role model since 2009, when he partnered with Youth for Human Rights International, a nonprofit advocacy group supported by the Church of Scientology, to channel his mountaineering passion into an even higher goal: helping young people understand and embrace the inalienable human rights of all people. Nardi visits schools in his native Italy and throughout Europe, promoting the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As part of his presentations, Nardi invites children to sign his “human rights flag” as a commitment to respect and promote the cause—and to date thousands of young people have. Nardi carries the flag when he climbs, and symbolically plants it at every mountain peak he reaches.

“It’s a way to disseminate human rights education in a different and effective way,” Nardi says. “My hope is that the younger generation is inspired by my example and that this helps them to get through the challenges of everyday life.”

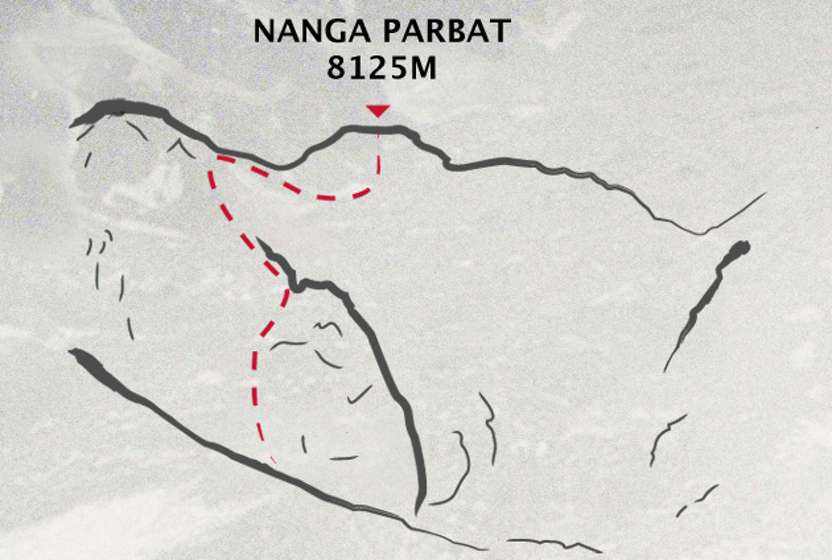

For Nardi, the challenge of a winter ascent of Nanga Parbat (which means “Queen of the Mountains” in Balti) began in January. It would require scaling what is essentially an immense wall of ice, with spectacular wind gusts and bone-chilling temperatures waging a persistent assault. And dealing with the lightheadedness, disorientation and hypoxia climbers suffer after extended periods at altitude.

“After days and weeks of extremely tough climbing, you essentially feel like you’re in a bubble where your every move is involved in survival,” Nardi says. “It creates a mix of internal joy and conflict that is difficult to describe.”

Nardi and his two climbing partners Alex and Ali would spend 88 days on Nanga Parbat, much of it at a base camp awaiting suitable climbing weather. But even when it came, conditions changed dramatically and abruptly, hindering progress. Several times, Nardi felt his life was in danger. One day an avalanche plowed into and decimated his tent—10 minutes after he’d stepped outside it. “That was my instincts working acutely for me,” he says.

On March 13, as the trio prepared to make their summit attempt, Nardi’s partner Ali began to show life-threatening signs of disorientation and hypothermia. They were just 300 meters from the peak but made the decision to turn back. “When we realized something was wrong with Ali, the decision was immediate,” Nardi says, “as life and responsibility are more important than anything else.”

But Nardi doesn’t consider the expedition a failure. He deems the outcome “very positive” and is proud that he, Alex, and Ali made it higher on Nanga Parbat during a winter climb than anyone in history.

“I lived an incredible experience since starting this quest,” he says, “one that made me grow as a man and as a mountaineer. It showed me that perseverance pays off. Even if we did not reach the summit, it was a fantastic climb full of great tenacity, perseverance, intelligence and strategy.”

Nardi has already received an invitation to return to Nanga Parbat for a fifth attempt, but isn’t sure he wants to, thinking he may be satisfied climbing mountains that peak below 8,000 meters. Nardi also hopes to explore Antarctica, Greenland, and the North and South Poles.

“I have a lot of projects in my head,” he offers, “but for now I want to rest.”