Listen to the Teacher

In late September, a dozen former Atlanta educators and administrators were put on trial in Fulton County Superior Court for conspiring to cheat on standardized tests and manipulate scores in that city’s public schools. The scandal cast a national lens on a case that could land the defendants, if convicted, in prison for up to 35 years. More than 180 educators at 44 schools are alleged to have been involved.

Then, in early October, the National Center for Fair & Open Testing (FairTest) reported that Atlanta “is the tip of an iceberg.” The group found evidence of standardized test manipulation in 39 states and the District of Columbia since 2009 and documented more than 60 ways schools roguishly inflated results.

Meanwhile, the most recent Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA, found that American 15-year-olds ranked 36th in the world out of 65 participating countries tested in math, 28th in science and 24th in reading. And measures to better student performance and literacy over the last decade and a half, beginning with No Child Left Behind, have only made things worse, experts agree.

Teachers have been scapegoated for the failure. The cover of the November 3 issue of Time magazine features an image of a judge’s gavel poised above an apple and the headline “ROTTEN APPLES: It’s Nearly Impossible to Fire a Bad Teacher, Some Tech Millionaires May Have Found a Way to Change That.” The perceived attack provoked an immediate, intense reaction from educators. An American Federation of Teachers petition demanding that Time make a formal apology gained more than 50,000 online signatures in its first 24 hours.

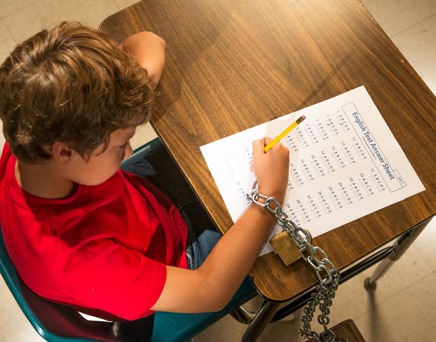

Pawning off the problem on teachers has helped give rise to a testing culture that narrowly defines educational success and threatens the livelihoods of schools and instructors when students, measured against the skewed standard, are perceived to underperform.

“Teachers are basically robots now,” charges Rodney Jordan, a sixth grade math teacher in Washington, D.C., and author of the book From the Heart of a Teacher. “It’s no longer about mastery of material or how much kids can learn. It’s about how they perform on federally mandated testing. All of the creativity, all of the innovation, it’s all out of the classroom and out of the teacher’s hands.”

How did it come to this?

You wouldn’t call a lawyer if you were sick. If you need legal advice, you wouldn’t go see a sanitation worker. So for educational issues, why would you go to everyone but the educators?

The No Child Left Behind Act, signed into law in January 2002, put U.S. public schools on the road to what many educators characterize as a gross overreliance on testing “technology,” which many believe has led to an overall compromise of American public school education.

The measure, which requires that all public schools receiving federal funding administer statewide standardized tests at all grade levels, ostensibly to prevent students from ‘falling through the cracks’—certainly seems well-meaning.

But critics say that, unwittingly (or not), No Child Left Behind left the education system vulnerable to mercenary interests. Illustrating that open door, Education Week reported that soon after the 2000 election, an executive of the British company Pearson Education boasted to Wall Street analysts that President-elect George W. Bush’s call for increased testing and school-by-school report cards “reads like our business plan.”

Pearson, based in London, is a publishing company that, at the time, specialized in textbooks and had annual sales of around $1 billion—little of it, however, generated in the U.S. Until the company aligned its corporate strategy—literally, it has been rumored—with No Child Left Behind.

“It became a capitalistic beacon for these people,” believes Bob Schaeffer, director of public education for FairTest, citing that starting in 2000—having caught a whiff of coming education reform—Pearson spent hundreds of thousands of dollars lobbying government officials.

Following its No Child Left Behind play, Pearson stepped up its efforts to sway policy decisions; the company’s lobbying expenditures between 2002 and 2012 topped $7 million—an investment that seems to have paid off, in spades. The company’s sales reached $9.7 billion in 2012 alone; Pearson is now said to be valued at $18 billion.

In that period came the implementation of the Common Core State Standards, in 2009. Common Core, as it is widely known, is a series of K-12 curriculum guidelines that standardizes on a national level what is taught and tested in math and language arts in U.S. public schools. Pearson is the primary supplier of Common Core testing and related material.

Adopted in 45 states and the District of Columbia to date, Common Core puts forth a universal set of standards to measure learning. Its professed, highly politicized agenda is ensuring that every high school student graduates “college and career-ready.“ It also recommends new “instructional strategies,” particularly for math. The Common Core formula renders simple arithmetic, for example, into a jumble of slashes, dots and boxes—making 6+4=10 something of an adventure.

Common Core may be benign in theory, but many educators obliged to work under the federally mandated benchmarks find it anything but. They have raised concerns, among them the possibility of profiteering.

“Common Core [seems] to advertise the fact that there is a huge amount of money to be made in public education,” says Karen Wolfe, a mother of two children in a Los Angeles public school and an education activist. “It told a lot of companies and organizations that there was a vast market sector to tap.”

“I mean, I don’t have a problem with companies making money,” Wolfe continues, “but if that’s the first concern for public education—to turn a profit—I have to believe your decisions are not always going to be what’s best for the students.”

No Child Left Behind and Common Core characterize an educational epoch of aggressive standardized testing for students and test-result based teacher evaluations tied to employment and salaries and to school funding—a climate that gave rise, many believe, to drastic increases in cheating.

Robin Lithgow remembers when it all began. The retired longtime Elementary Arts Coordinator for the Los Angeles Unified School District could hardly believe that standardized testing would be the primary yardstick to measure a child’s educational growth and determine their future.

“As soon as No Child Left Behind went through, testing suddenly became this god of education,” she recalls, “and it only intensified under Common Core. We were actually trained in how to bring up the test scores! As if this had anything to do with knowledge! But the money it reaped completely drowned out our voices saying, ‘This isn’t how children learn.’”

The pressure for schools to perform leads some to encourage slow-learning and poorly performing students to switch schools or be pushed for tutoring in advance of a key exam, according to Heather Mills.

When she was a math teacher in North Carolina, Mills recalls being asked which of her students were in danger of failing the end-of-grade math test. After replying that none were likely to fail, she was asked to name any children who might be “at-risk.” Reluctantly, she did.

“The next week, both of these kids were removed from my class for tutoring by parent volunteers, resulting in their public embarrassment at being labeled slow,” Mills says. “Both kids wound up passing the test, but that situation played a major role in my leaving the public education system.” She now runs her own private tutoring business.

Stories like this are what drove Jordan to write his book; From the Heart of a Teacher argues that standardized testing puts the focus everywhere but where it should be—on the children themselves.

“A ridiculous amount of our time is taken up by teaching to the test. [But] it isn’t as if the tests matter for anyone but the people who worry about money and standing,” Jordan maintains. “Kids can fail every single standardized test from third through eighth grade and still get pushed forward to the next grade.”

Jordan also cites a 2013 study that found only 26 percent of high school seniors tested on grade level in math and only 38 percent in reading, a significant drop from 20 years ago.

“This is the bottom line: It’s not working,” he says.

A failing education system in the United States has significant and widespread impact—on children, on the nation’s economy, and on the larger society.

A 2014 One World Literacy Foundation study concluded that two-thirds of students who can’t read proficiently by the fourth grade will end up in jail or on welfare. More than 70 percent of America’s prison inmates cannot read above fourth-grade level.

The U.S. Department of Education reports that 6 percent of females and 7 percent of males failed to complete high school in 2012, or about 1.3 million all told. The annual societal tab in crime and public welfare from the lack of a high school diploma was calculated by the National Dropout Prevention Network at approximately $24 billion for men alone—this a decade ago, in 2004, the last time a calculation was offered, a number that has certainly risen significantly since.

The issue of why it’s not working is a complicated and contentious one; there’s no answer that’s simple and sure. And while Common Core, No Child Left Behind, and the body of institutional reform methods have many vehement critics, even they agree the problem is multifaceted.

Jeaninne Escallier Kato, a teacher who recently retired following a 36-year career in Sacramento public schools, believes the timing of Common Core was unfortunate in that it coincided with a rise in kids’ sense of entitlement and a lowering of the parental bar.

“Teachers can’t just teach anymore,” Kato says. “They also have to be policemen, counselors and parents. Meanwhile, the kids think they have everything coming to them.”

Meanwhile, a privatization movement is underway that has resulted in the closing of thousands of public schools while an equally large number of publicly-funded but privately-run charter schools open on a for-profit basis. Nationwide, 300,000 teaching positions were eliminated between 2009 and 2012, according to Investing in Our Future: Returning Teachers to the Classroom, published by the White House.

Also on the rise: the profile of billionaire philanthropists, who use their money and influence to drive a seeming privatization agenda in the guise of school reform.

Among the wealthy funders using their influence to drive the new public education movement: the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (estimated to have spent $2.3 billion on Common Core initiatives), the Eli and Edyth Broad (rhymes with road) Foundation, and the Walton Family Foundation (the charitable arm of the Walmart empire).

“These are all free market ideologues who want to see a private market for public education, to the detriment of schools and students,” believes Schaeffer.

One could also question a company based in England (Pearson) setting standards for students an ocean away. Yet Pearson remains the driving force in Common Core evaluation despite the cheating explosion and claims that its products are “widely misused,” says Schaeffer.

It all leaves Rodney Jordan shaking his head in frustration.

“You wouldn’t call a lawyer if you were sick,” he says. “If you needed legal advice, you wouldn’t go see a sanitation worker. So for educational issues, why would you go to everyone but the educators? We’re the people who spend hours in the trenches every day. I just don’t understand why the Department of Education on the federal level as well as each state is investing billions of dollars in people who have no idea what goes on in the classroom.”

Jordan is hardly alone. Education experts around the country question the involvement of Pearson and big-bankroll nonprofits, and also why standards that are so developmentally out of synch—pushing young children to absorb information beyond their grasp—have been so zealously instituted.

Some believe the problem is more fundamental, rooted in the very existence of public schools. J. Allen Weston, executive director of the Home Learning Association (America’s only national homeschool association serving a growing contingent of homeschoolers) advocates eventually replacing the entire public school system with what he calls “self-directed learning centers.”

Critics also cite a marked overemphasis on technology in the Common Core paradigm. One of the most staunch advocates for testing, former Los Angeles Unified School District Superintendent John Deasy, attempted to push through a plan to provide an iPad to every L.A. public school student, teacher and campus administrator at a cost of $1.3 billion, while at the same time firing teachers and cutting classroom supplies in the name of cost savings. When the proposal turned into a fiasco, Deasy was forced to resign in mid-October.

It’s no longer about mastery of material or how much kids can learn. It’s about how they perform on federally mandated testing. All of the creativity, all of the innovation, it’s all out of the classroom and out of the teacher’s hands.”

“Many of the problems in society begin with public schools,” says Weston. “Grades and testing are completely the wrong way to go in terms of teaching children anything. All studies show that the way children learn the best is by exploring things on their own time and in a way that’s meaningful to them. And public schools are exactly the opposite: A packaging plant that treats children as empty vessels.”

It would seem there is no shortage of voices on the problems bedeviling education in the United States. Fortunately, there are just as many trumpeting solutions—and all agree they would rather talk about those.

Even the staunchest critics know it’s not realistic that Common Core will be dismantled anytime soon. Still, there are ways to improve the efficacy of public education.

Retired teacher Kato feels it needs to begin at the political level.

“I think every politician, Democrat or Republican … must be made to spend a month sitting in a classroom and observing what goes on before being permitted to run for an education position,” she says. “Seeing for themselves the reality of what teachers have to deal with day after day would make a huge difference, I have to think.”

Dr. Genola Johnson, executive director of the G.A. Educational Learning Center in Peachtree City, Georgia, works in her job as an educator and consultant to teach kids not just how to be better students but how to prepare to be adults in the world of the future.

“We need to focus far less on testing and incorporate critical thinking skills,” she says. “If [educators are] really committed to preparing students for the work force, critical assessment is what really counts. We really don’t need bank tellers, cashiers or any job that requires repetition. The future will be about real decision-making.”

There also has to be a way to eliminate the authority exercised by interests not directly involved in learning and instruction, Jordan maintains.

“We need to remove everyone from the process who isn’t a direct part of the student equation,” he suggests. “Get rid of the profiteers. Get rid of Pearson. Tell them, ’No thank you, we don’t need your help anymore.’”

“Then identify the successful teachers who work with kids who come into the seventh or eighth grade at a fourth grade reading level and are able to get them up to speed. Use those teachers to generate a curriculum and create an environment that’s far more conducive to learning.”

That means getting teachers involved in a far more meaningful way than they typically are under Common Core, where he says their primary role is as implementers of prepackaged data. They have been largely minimized in the present system, their respect diminished, their jobs perpetually in jeopardy.

“Teachers must be recognized as leaders if learning is the real goal,” Jordan adds. “Once you do that, you boost morale. And when morale gets boosted, it’s contagious.”

Professor Mark D. Naison of Fordham University, co-founder of the Badass Teachers Association movement that has taken the teaching community by storm (see Profile), believes that the solution lies in liberating classrooms from a repressive culture of testing—one that has effectively tripled the number of standardized tests grade-schoolers must take.

“There needs to be a literal revolt against the test,” Naison says, “a massive test refusal on the part of students and families. There needs to be a massive reduction in both the number of tests and the unbelievable expense of them. Let’s start a number of test-exempt schools that evaluate students using a different model. And there needs to be a stop to the evaluation of teachers based on those tests.”

Naison’s last point is gaining wider acknowledgement. Undermining the picture painted on the magazine’s cover, the November 3 Time story reported that in June the Gates Foundation called for a moratorium on linking test results with teacher evaluations based on Common Core standards until 2016. In August the Department of Education announced that states could put a moratorium on tying student test scores with teacher assessments until 2016.

Naison further recommends a renewed focus on arts education, sports and hands-on science, along with a reduction in class size. Only then can the effects wrought by Common Core—which he calls “The most destructive bipartisan policy in the United States since the Vietnam War”—begin to truly be reversed.

We need to focus far less on testing and incorporate critical thinking skills.

He also suggests reviving vocational and technical education. “We used to have all of these really good vocational schools across the country, and that sort of education is hugely valuable,” he stresses. “I’m not sure why they went away.”

For Samuel Blumenfeld, author of the 1999 book Alpha-Phonics: A Primer for Beginning Readers, the secret to solving the education crisis is as simple as teaching the proper phonetic reading method to young children rather than what he terms “the low-literacy process” favored in most schools.

“Phonics teach children to speak in their own language and develop a huge vocabulary early on,” Blumenfeld believes. “To teach reading any other way leads to frustration and learning disorders like ADD and ADHD.”

Many of these ideas already are part of the curriculum in private and alternative schools, where there exists a spirit of experimentation. Naison, for one, has seen many successful schools in New York City that eschew testing in favor of assessing the full learning needs of the child.

“We need to vote in officials who support real learning and vote out those who don’t,” he says. “That’s another part of the solution. Put only those who agree to change the system in elected office. They need to be working for us, not the government.”

There are a few more points on which all engaged in the education debate agree: It isn’t too late to turn things around. And if there is a groundswell of support to implement the right kind of reform, it will happen.