PART 5

This is the fifth of a seven-part exposé of the exploitation of children for sex by the classified ads portal Backpage.com. Click here to see the previous installment.

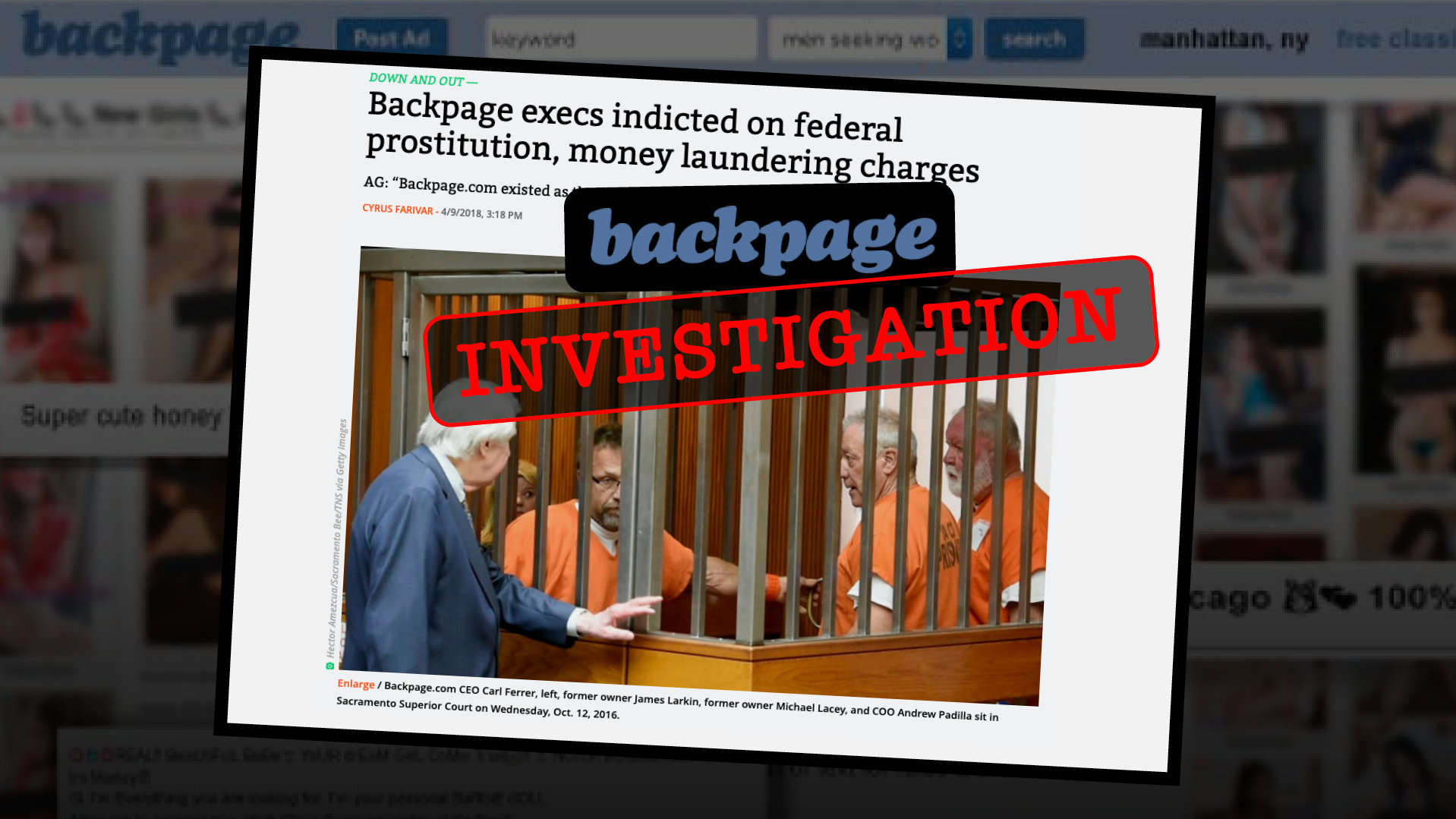

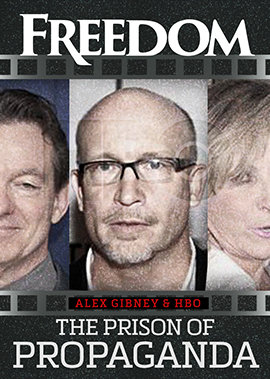

As far back as 2011, when the Village Voice was reaping some $22 million annually from Backpage’s prostitution ads, Larkin and Lacey unleashed editor Tony Ortega to attack critics who were shining a light on the website’s pimping and child sex trafficking, according to a former Voice employee. One of the most prominent of those critics was the Church of Scientology.

As protesters marched with signs outside Village Voice offices in New York, and visited state’s attorney generals around the country, columns by Ortega, and an “investigative” series his reporters produced under his direction, lambasted reports of the epidemic of child prostitution as “bogus information.” What’s more, the columns lashed out at people combating child sex trafficking as “fatuous and silly.”

Ortega’s tone was mocking and derogatory, a hallmark of much of his “journalism.” And his counter-attacks came in particularly useful for Larkin and Lacey, who had promoted Ortega to the top job at the Village Voice after he’d worked for their chain for decades in undistinguished roles. On at least two occasions, he had been outed by journalism organizations like Columbia Journalism Review for writing wholly invented stories as if they were fact—in one case a story mocking the victims of a vicious sexual assault.

Insiders at the Village Voice, including veteran reporter Wayne Barrett, in an interview in the year before he died in 2017, told Freedom that Ortega was also a poor manager and was considered an ill-conceived choice as editor-in-chief. He was not liked by the paper’s staff, and a number of noted staffers resigned over what they characterized as mismanagement by the paper’s ownership group—which included bringing Ortega out of obscurity to take the job. He was named after a string of better-known editors were hired and who then quit or were fired by the paper’s owners. Ortega apparently proved more compliant.

What’s more, the Voice’s new management buyout group disapproved of Ortega’s attack journalism, use of questionable and unreliable sources, and promotion of salacious stories of doubtful veracity. Sources said the story circulated that the management group, seeing Ortega as a liability, had quietly demanded Larkin and Lacey fire Ortega before they took over the paper. And Ortega was ejected, trading his mantle of editor for a life of a bedroom-blogger.

Ortega’s prime deceit—and that of his bosses, who supported his diatribes and lies—was the contention that Backpage was only acting as a community bulletin board for consenting adults and had no idea or interest in what happened after people found each other through its ads. But as congressional investigators, prosecutors and untold numbers of citizens since concluded, Backpage not only did know what happens when adults barter sex in classified ads, but the company knew perfectly well about the horrors that awaited children when they are purchased.

The words that Backpage deleted from ads, both manually and with the help of automated electronic filters, include “Lolita,” “teenage,” “teen,” “rape,” “young,” “amber alert,” “little girl,” “fresh,” “innocent” and “school girl.”

According to the Senate report, “by Backpage’s own internal estimate, by late 2010 the company was editing 70 to 80 percent of ads.” Put another way, Backpage sanitized the content of innumerable advertisements for prostitution and for trafficking of minors. And by doing so, the Senate report concludes, it lied to the public and the courts that “it merely hosted content created by others."

Not only was Backpage manipulating ads, an official of a prominent human trafficking organization told Freedom that the site also refused to take down ads trafficking “missing” minors and took down ads that attempted to throw a lifeline to kids trapped in sex slavery.

“They [Backpage] actually engaged in assisting traffickers in posting ads that would evade law enforcement and avoid referrals to NCMEC (National Center for Missing and Exploited Children), which Backpage is required to do,” argues Erin Andrews, director of policy at FAIR Girls, the Washington, D.C., anti-trafficking nonprofit.

“We get a lot of really young girls—11 to 16 years old—in our program, and the vast majority of them have been sold on Backpage.com at least once if not multiple times,” Andrews explained. “For years, our executive director [Andrea Powell] went looking on Backpage for ads for girls who had been missing. Sometimes she would find the girls in ads on the website and would report the ads to Backpage, but Backpage would regularly refuse to take down the ads.”

Frustrated by this behavior, FAIR Girls bought ads on the website offering sex trafficking victims helpful tips, such as hotline numbers. But Backpage took all of these ads down, according to Andrews, further proving that the website does control and even edit content.